Princesses, Lovers, Saints, and Les Galeries des Dames

Before—well before—Forbes’s “World’s Most Powerful Women” lists and Vogue’s “Women in Hollywood” covers, there were the Galeries des Dames.

Modeled after the classical compendiums of the great gods, kings, martyrs, and heroes, these lists of goddesses, queens, saints, and heroines sought to round out the reader’s knowledge of ancient history and capture something of the enduring psychology of the current female.

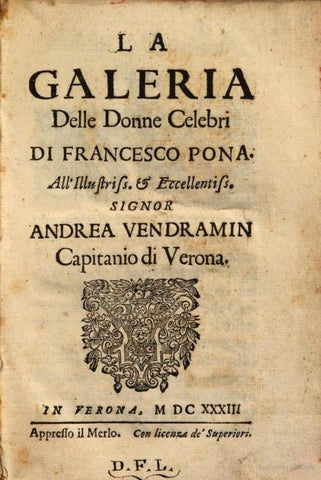

In 1633, the Italian doctor, poet, and libertine Francesco Pona wrote the La Galeria delle Donne Celebri (The Gallery of Famous Women), a series of twelve embellished accounts of four lovers (including Helen of Troy and Semiramis), four chaste women, and four early Christian-era saints.

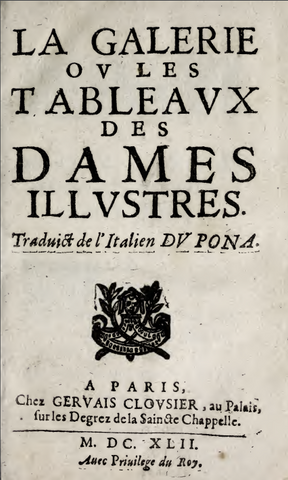

In 1642, the book enjoyed a loose French translation, La Galerie ou les tableaux des dames illustres, by François de Grenaille, who claims to have expurgated Pona’s text for the sake of decency—but he nevertheless wrote scenes of opulence and passion in such a way that encouraged the reader to imagine the rest. The trick, you see, was to meet the dual goals of “educere et placere”—to educate and to please—by mixing just the right amount of edifying historical and hagiographical biography with the exciting, seductive, and sometimes horrific bits that would provide readers with frissons of delight.

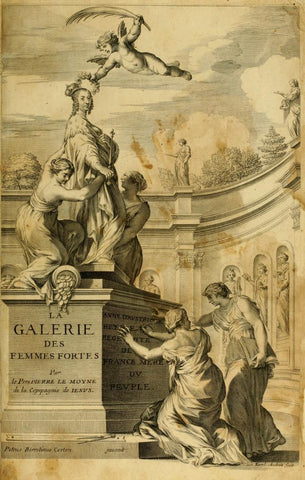

In 1647, the grandiloquent, pedantic, and (one assumes) pretentious Pierre le Moyne de la Compagnie de Jesus wrote La Galerie des femmes fortes (The Gallery of Strong Women), divided into chapters of “Les Fortes juives” from the Bible, “Les Fortes barbares” from the ancient world broadly, “Les Fortes romanes” from Ancient Rome, and “Les Fortes chrétiennes” from the intervening years, including Joan of Arc and ending with Marie Stuart. He begins by defending his decision to write about females, since females are needed to give birth to males. Each entry comes with a helpful moral question, such as whether great women are capable of true philosophy or of heroic virtue. I can think of few people I’d be less inclined to invite to my imaginary dinner party.

On the other hand, I would most definitely send a fan-girl invitation to the “Granddaughter of France”, Anne-Marie-Louise-Hortense d’Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier. She lived an eventful life from 1627-1693 as the granddaughter to Henry IV and the wealthiest unmarried heiress in France. She was an active participant in the French civil war known as La Fronde and she had her hopes of marrying the man she loved refused by Louis XIV, thereby making her a spirited and tragic heroine in her own right, about whom Madame de Lafayette (most known for La Princesse de Clèves, about which I’ve written elsewhere) wrote a novel called La Princesse de Montpensier. But she was also on the other side of publishing as the author of not only her famous Mémoires, but also of Divers portraits, La Galerie des portraits, and Portraits littéraires, which were collections of accounts of famous figures in history—many of which are female—penned by themselves, close acquaintances, or Montpensier herself. These anthologies were the Who’s Who of the 17th-century literary gallery.

In 1790—notice the date—appeared the third volume (I can currently find no trace of the first two online) of La Galerie des dames françoises (The Gallery of French Women), by Jean-Pierre-Louis de Luchet, who was, prior to the Révolution, known as the Marquis de la Roche du Maine. He was a French journalist, essayist, and theatre manager who knew how to pivot to keep his head. The introduction to his Galerie is an interesting account of the mood in 1790, when the promises of the great Révolution were giving way to the realities of the Terror, and Luchet expressed his desire for moderation. As the goal of the Révolution was to cut ties with the past, it’s not surprising that Luchet’s Gallery of women does not feature actual women. Instead, they are a series of almost allegorical character “types” of women that one might come across in the France of his day: the haughty, overly educated Statira, the lazy, self-indulgent Marthésie, the naturally intelligent paragon Desdémona, the cool and indifferent Sapho….

As far as social commentary goes, they seem to be grounded in the French tradition of La Rochefoucauld’s Maximes, La Bruyère’s Caractères, and the habit of giving names like "Sia" and "Lady Gaga" to salon women of the previous century, but they also remind me a little of the Myers-Briggs accounts of personality types as well as Jungian-influenced interpretations of myths. Readers certainly would have enjoyed finding the good qualities in themselves and the bad qualities in others!

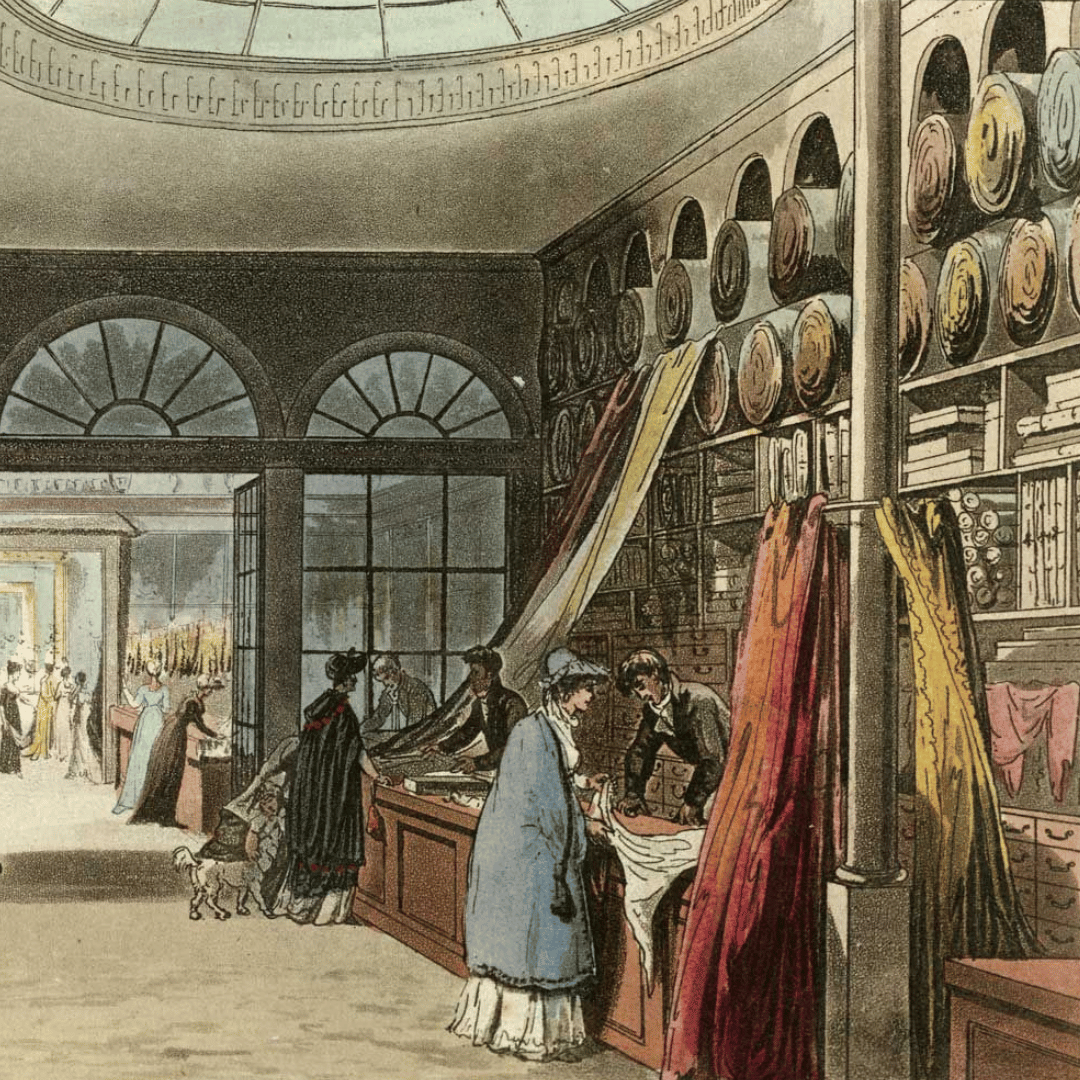

But while you’re flipping through the pages of whatever insipid magazine it is this week (don’t get me wrong–I occasionally love a good bad magazine), save a sigh for the bygone era of the salons:

“Le salon, on le sait, était le principal théâtre de l’ancien régime. C’est là, dans des conversations rapides; c’est au milieu des petits soupers que les opinions nouvelles se fixaient. Les femmes y tenaient l’école du savoir-vivre, et leur exemple, les traditions élégantes que conservaient les plus âgées, les rendaient l’objet de l’empressement de toute la jeunesse distinguée; c’est sous leur influence qu’une bonne éducation s’achevait.”

“As we know, the salon was the main stage of the Ancien Régime [the French court before the Révolution]. It was there, during the rapid-fire conversation; there, during the little dinner parties, that new opinions materialized. There, the women held the School of Life, and their example, the elegant traditions that were upheld by the eldest, were eagerly pursued by all the youths of distinction; it’s under their influence that a good education was achieved.”

So. I decided to do my own Galerie des Dames: a series of 9 small oil portraits of very feminine but very strong women: Patience, Honoria, Victorine, Felicity, Celestine, Benedetta, Hero, Allegra, and Prudence.

Rather than written portraits, they're painted portraits, but just as with the anthologies they come with a heavy sense of story. These are ladies who possess—or so they’d like us to believe—the courage of the legendary heroines, the poise of the classical goddesses, the steadfastness of the martyred saints, the universality of the Revolutionary allegories, the specificity of their own circumstances, and, most of all, the romance of their unwritten stories.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.