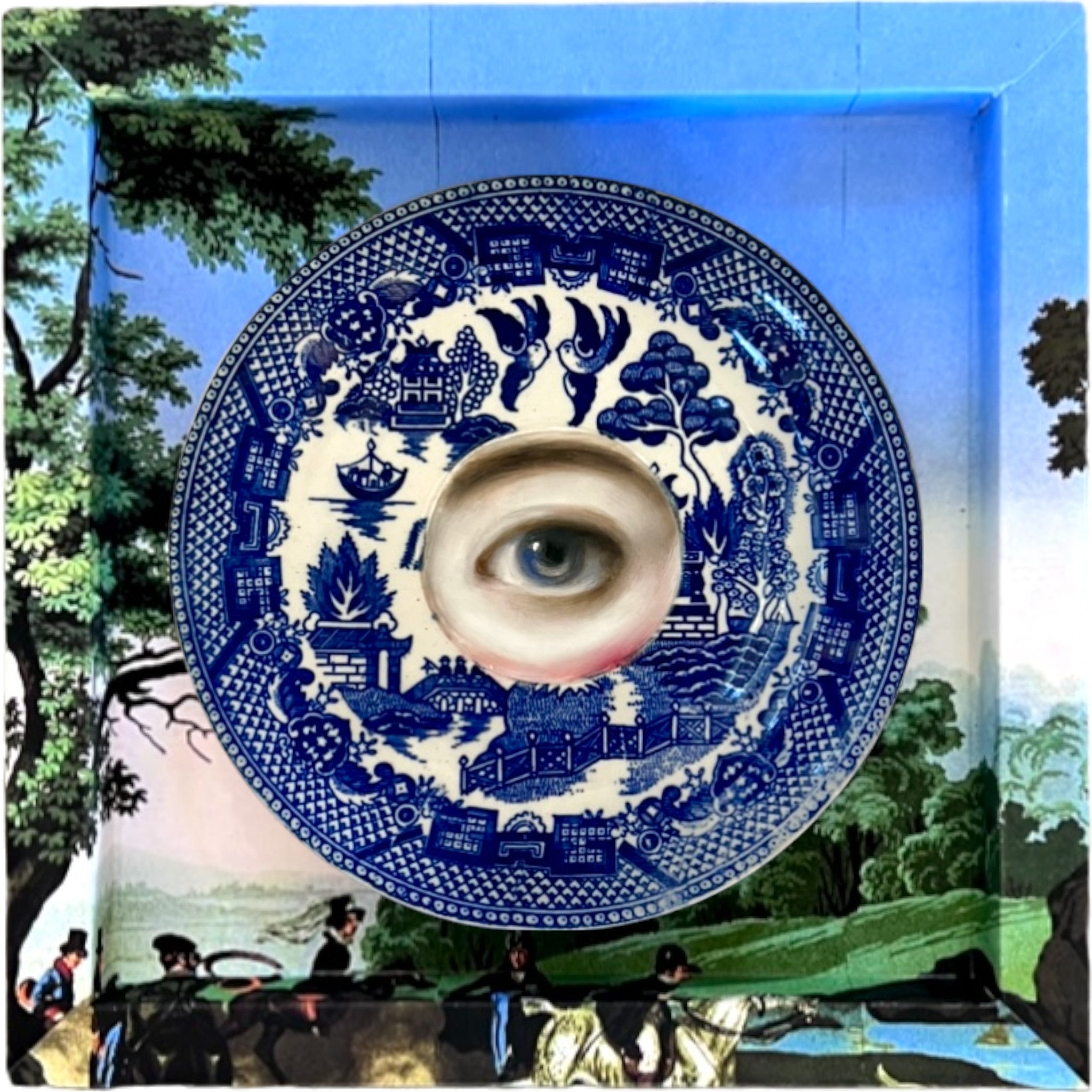

"WHY DO YOU PAINT EYES ON PLATES?"

"Why do you paint eyes on plates?" My mother's friends sometimes ask me this. They want to be polite and so they struggle with the question for a minute or two, but in the end they can't resist asking anyway.

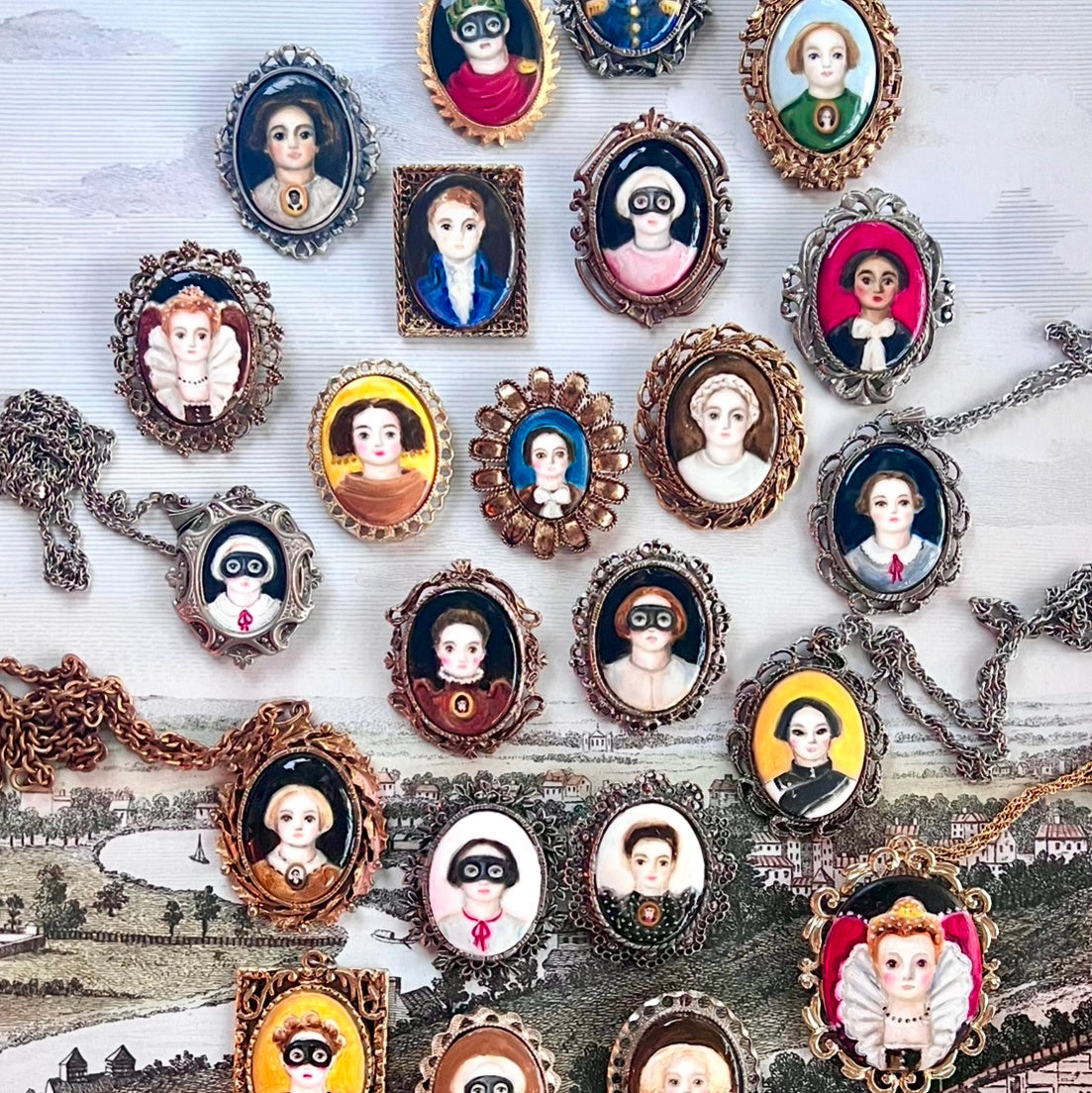

"The short answer," I say, "is, honestly, 'I don't know'. The longer answer has to do with the fact that I love history, and I love stories, and I love the Georgian tradition of painting itty-bitty eyes on ivory and setting them in brooches so that everyone knew you had a lover but no one knew who it was. And I love antiques, and I love orphaned antiques especially, and one day I came across some pretty little saucers when I was looking for some smaller antique frames for the Lover's Eyes I was painting, and my brain is the sort of brain that puts things together, and I thought, 'it wouldn't hurt to try', and so I tried, and I was startlingly pleased with the result, with the saucer bringing the eye to life and the eye giving the saucer new life too...."

And at about this part in the explanation, some of her friends wish they'd never asked, and others of her friends tell me about their mother's antique china.

Now, to be completely honest I cringe at the words "upcycled" and "repurposed" and in general I'm not very interested in craft projects to do with old cups and saucers - pouring candles or planting succulents in them, making lawn totems sculptures by stacking them, etc. I'm sure plenty of it is lovely and done well, but it can also be a bit twee.

But I do love collecting antiques as if they were rescue dogs, and giving them baths and restoring them and tilting my head and looking down at them and asking, "Now, what are we going to do with you?"

My mother always says that one ought to do the minimum when it comes to restoration. She is a retired antique dealer, if one can retire from such a profession. If an antique dealer buys and at least sometimes brings herself to sell antiques, a retired antique dealer just shamelessly buys antiques. But having been in the business for decades, she has come across a wide variety of poor decisions regarding restoration, including the use of glue guns, sharpies, bad varnish, latex paint, shortened table legs, and the like.

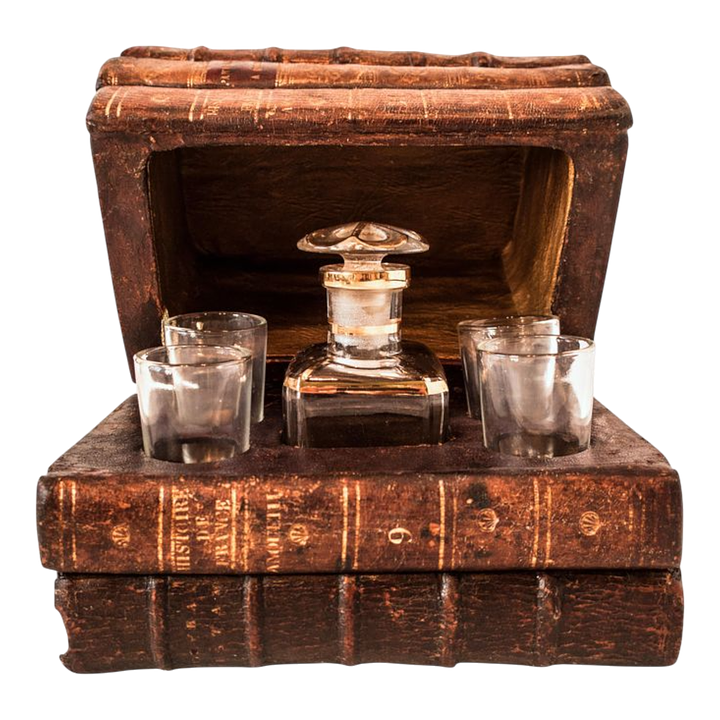

There are a few old restoration moments which are acceptable, such as old pottery staples, metal pottery patches, kintsugi, hidden book boxes, adding shelves to cabinets, and the occasional transformation of a vase or figurine into a table lamp.

The charm of these interventions usually comes from their age, e.g., a favorite 18th-century Chinese Export Porcelain saucer was broken by a clumsy suitor come to tea in the 19th-century and taken to a repair shop, where metal staples were carefully inserted to put the saucer back together. If an unread liturgical treatise of 1735 was carved out and used to hide a pack of cards or pound notes in 1785, then the sin against the book was absolved long ago; carve out a 300-year-old book today and it’s sacrilegious!

Newer restorations, when necessary, must be perfect or they lack all charm. My mother once had a family house sit while we went to France, and their cat ran mad around the house and broke one of a pair of early Delft polychrome cows. The woman had the tact (and money) to take the tiny pieces of the cow to a repair shop, where it was meticulously reassembled and refired, and now the untrained eye couldn’t tell the difference between the two cows.

I’ve gone a bit off-track, but all this is to say that I’ve been conscious my whole life of the very delicate poetic balance of what to do about broken old things in the modern world.

So while I love the goal of attempting to make what would be, at worst, discarded or, at best, mediocre antiques exceptional, at the same time I’m constantly flooded with the guilt of having interfered with them too much, as well as the anxiety of having possibly tipped over into tweeness myself. One can’t really be serious about painting portraits on old plates, so I find myself leaning in to that sense of “why not?” and “what next?” and “what if?” with portraits heroines that live within the romantical, imaginary wreaths of the borders. “Life” – and art too, I would add to Oscar Wilde’s quip – “is much too important to be taken seriously.”

Do my paintings work? Well, I hope they do, at least some of them; and when I know they don’t work I soak them and scrub them off. So while the paintings can be preserved and maintained if desired, they can also be ctrl-z’ed as if they never existed, and the antiques can go back to being what they were before. Perhaps they’re just a chapter in the life of these antiques that have lived for decades and centuries before us, and will go on to have other lives and meanings and metamorphoses after us too.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.