The Wooing of King George IV & the Origin of Lover's Eye Jewelry

From 1785-1830, Lover’s Eyes were painted on small pieces of ivory, set in jewels, and worn as brooches pinned close to the heart as cherished talismans, clandestine proclamations of love, playful social guessing games, and the metonymic possession of the distant or departed beloved.

Although miniature portraits have existed roughly since portraits themselves have existed, miniature portraits of loved ones enjoyed particular popularity from the Renaissance onward, and were used as introductions, gifts, and mementos.

Lover’s Eye miniatures - just the eyes - seem to have originated in France. “On December 6, 1785,” writes Elle Shushan in Lover’s Eyes: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection, “the eccentric Lady Eleanor Butler recorded that a friend, recently returned from the Grand Tour, had brought back ‘an Eye, done at Paris and Set in a ring; a true French idea and a delightful idea which I admire more than I confess for its singular Beauty and Originality’” (p. 16).

It was in England, however, that the fad took off, thanks to the Prince Regent, the future King George IV, who was a notorious dandy and copied many of the latest fashions from France.

In 1784, he went to the opera and fell madly in love with the twice-widowed Maria Fitzherbert.

According to British law he could not legally marry her because she was a Catholic, and she adamantly refused to be his mistress. She fled to Paris, but he continued to woo her (even feigning suicide), and on November 3, 1785, sent a letter with a postscript to say that he had sent her “a Parcel, and at ye. same time an eye, if you have not totally forgotten ye. whole countenance, I think ye. likeness will strike you.” They eventually married in secret and exchanged Lover’s Eyes. The fact that she could only be his morganic (not technically legal) wife made the love story all the more devastatingly romantic. His love for her never waned, and in addition to the initial Lover’s Eye he had many more typical miniature portraits painted of her. In his will he requested “that my constant companion, the picture of my beloved wife, my Maria Fitzherbert may be inter’d with me suspended round my neck by a ribbon as I used to wear it when I lived & placed right upon my heart” (Shushan, p. 34): it was indeed buried with him, and it is with him to this day.

Here is the Lover's Eye miniature of Maria Fitzherbert:

As a result of this illicit, high-profile relationship, the craze for Lover’s Eyes took off. Although for the most part the paintings (watercolors on ivory, and sometimes gouache on card) were set in pins, brooches, and lockets, they were also occasionally set in rings and jewelry clasps, as well as in and on snuffboxes, patch boxes, toothpick cases, watch keys, book covers, dance programs, and even a coffee cup. The lockets could be doubly interesting, since they frequently held the painted eye on one side and a braided or woven lock of hair on the other: the former a pictorial, the latter a physical synecdoche (part for the whole) of the lover. In these, the reliquary function of the eyes was heightened to an almost sacred devotion.

If miniature portraits were complicated with their symbolism, sentimentalism, and synecdoche, Lover’s Eye portraits were even more so. By cropping the portrait to a single eye, a few things happened. First, the portrait ceased to be easily identifiable: only the beloved or those who were otherwise close to the beloved would know his or her identity. The portrait was less a public, factual, accessible depiction and more a private, intimate, shared secret. If a Lover’s Eye was displayed, it was a bit of a social tease: here’s a portrait of someone, but you don’t know of whom.

Second, by framing the eye – a point made in great detail by Hanneke Grootenboer in Treasuring the Gaze – the object becomes a subject looking out at the subject. In simpler words: are we looking at the painting, or is the painting looking at us? Most of the Lover’s Eyes are gazing out directly at the viewer (these, she says, are 1st-person “I” eyes), although a few are three-quarter or in profile (the 3rd-person “he” or “she” eyes). When comparing the two, you can fully feel the impact of the direct lover’s eye, engaging you in a way that’s somehow beyond what’s possible in a typical painting.

Third, a point I’ve not seen made anywhere else, painting an eye – just an eye – and encasing it in jewels is extravagant, whimsical, and somehow extremely clever and full of wit.

The intensity of a Lover’s Eye painting is undeniable. Looking at one, you can’t help but notice the simplicity, understand that it’s pure artifice, appreciate the technique, and acknowledge that, on the whole, it’s rather silly – and yet nonetheless be sentimentally tricked by the trompe l’oeil and find yourself engaging intimately, beyond words, with whatever timeless soul is residing in the little frame, and wondering what other thoughts it has, and hopes and dreams, and being filled with the warmth of companionship and connection as you feel an inexplicable urge to share your own thoughts and hopes and dreams with a patiently listening and most keenly observing soul. I might be overstating things. But there is a flicker of something deeply human that brightens us from inside when we encounter a Lover’s Eye – whether of a stranger or of a familiar beloved.

This magical quality, coupled with the sacred overtones, gives a certain talismanic quality to Lover’s Eyes worn as jewelry. This is more than the intimate gaze of two lovers connecting from pillow to pillow: this is a gaze that transcends time and reality, and seems to take on the otherworldly powers of the all-seeing eye or the protector eye. Unlike these abstracted powers resident in the different forms, across different cultures, in variations of the evil eye, however, the Lover’s Eye has one foot in this world and one foot in the next. As the lightness of the Georgian Era gave way to the darkness of the post-Albert (1819-1861) Victorian Era, Lover’s Eyes gradually came to be less, on the whole, about passion, and more about friendship and family, insuperable distances, and holding on to some seemingly living part of a loved one even after death. Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Lover’s Eyes long after their trend had given way to the hair jewelry memento mori more common during the latter 19th century.

Lover’s Eyes are difficult to classify as artefacts: they’re jewelry and art, and as art they’re portraits, symbols, and abstracts. As such, although the renowned painter Richard Cosway (1742-1821) painted the Lover’s Eyes of King George and Lady Fitzherbert, he painted few others: artists considered them novelties beneath their renown. Most Lover’s Eyes were painted by anonymous miniature portrait painters who hopped on the trend, and some were employed by jewelers who supported in-house Lover’s Eye portraitists.

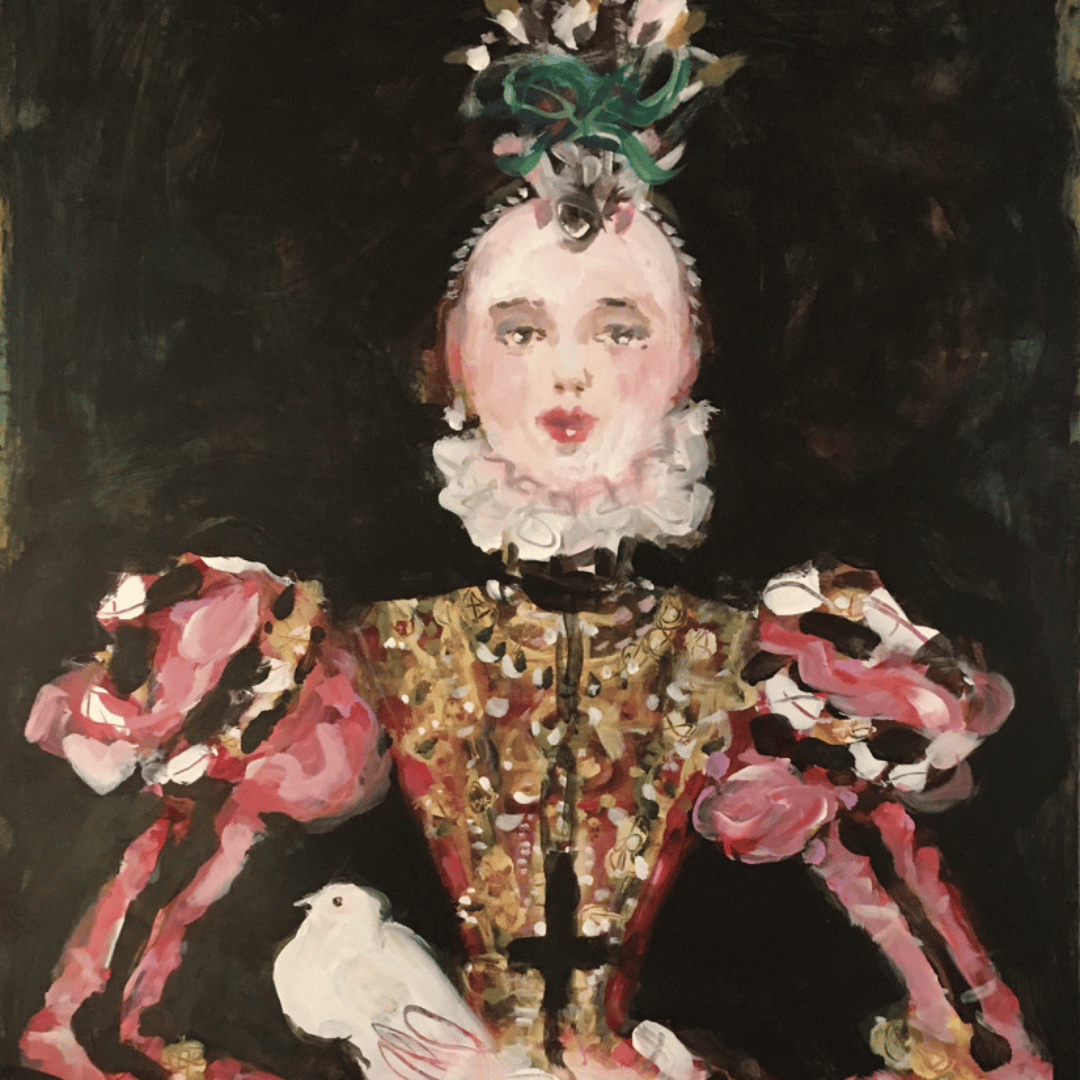

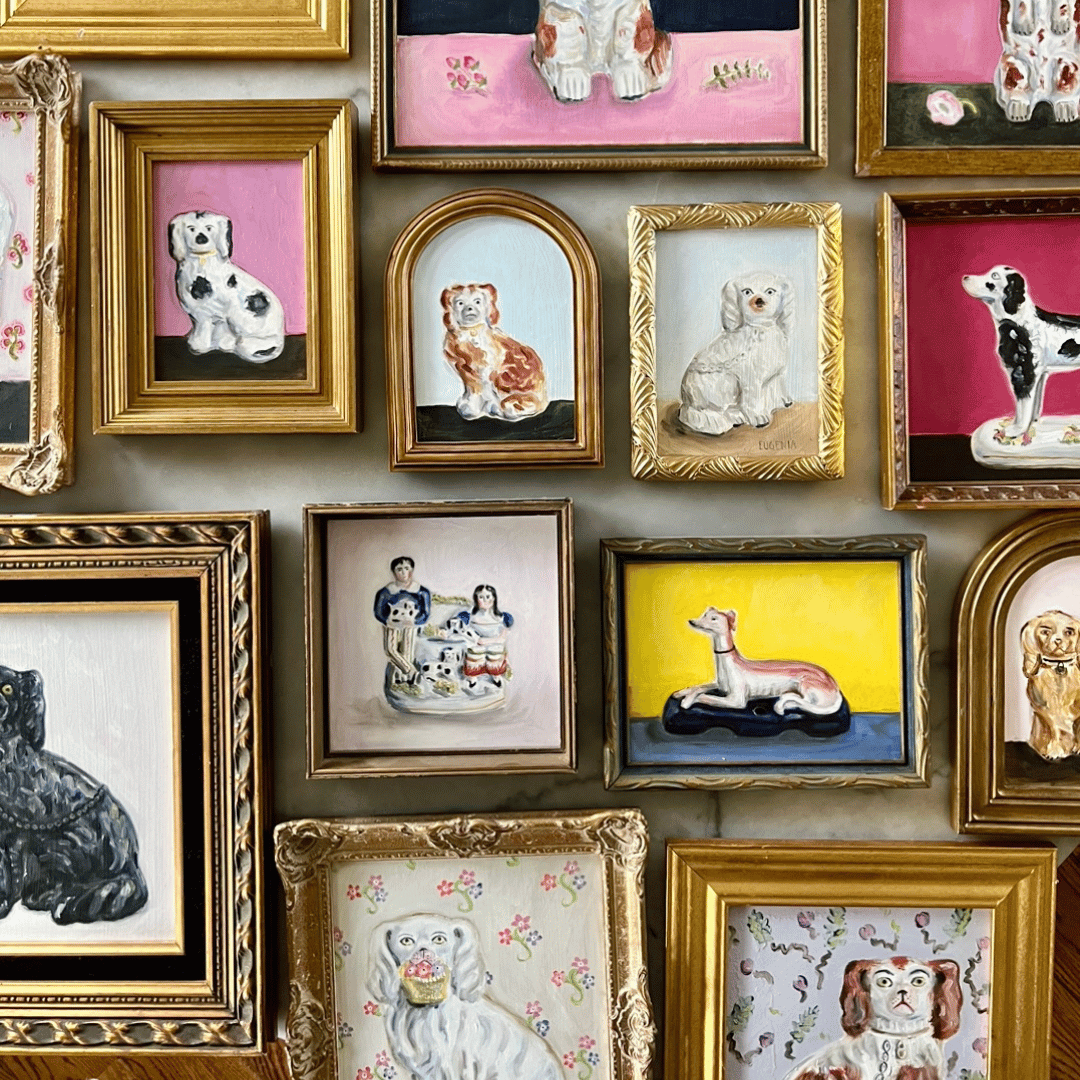

In my own paintings I’ve attempted to revive this long-lost craft, in the tiniest of bejeweled settings to the largest of antique gilt frames, with eyes that – when I’ve done it right – sparkle just as the originals do with secrets, warmth, and wit.

Guide to Lover’s Eye jeweled settings (summarized from an essay by Graham C. Boettcher in Lover’s Eyes, p. 39ff):

Pearls: purity, innocence, humility, tears

Diamonds: innocence, life, joy, strength, constancy

Coral: repels misfortune, harm, evil eye

Garnet: felicity, constancy, friendship

Turquoise (rare and expensive): true riches, changes color according to health

Amethyst: faith, protection, sincerity, trust unto death

Topaz: faithfulness, friendship, prevents melancholy, love

Onyx, Whitby jet, French jet: love beyond death

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.