King Charles, a Secret Seaside Love Affair, and Staffordshire Spaniels

The following is an article I wrote for Victorian Homes (February, 2010) (with new images).

Staffordshire spaniels are an odd breed of antique. As far as dogs go, they neither snuggle nor bark; and as far as antiques go, they have no real household use. So what accounts for their enduring popularity?

Staffordshire spaniels come with all sorts of stories.

When my mother visited a small seaside town near Southport, an old English woman recounted a local legend. Once upon a time, in a little bungalow next to the sea, there lived a woman and her two Staffordshire spaniels. She was careful about the placement of her spaniels in the front window. When her husband was at home, she placed the spaniels with their backs to each other. When he went to sea, she turned them so that they were facing. The woman's lover would pass by the house, note the orientation of the spaniels, and know whether or not he could sneak in for a snuggle.

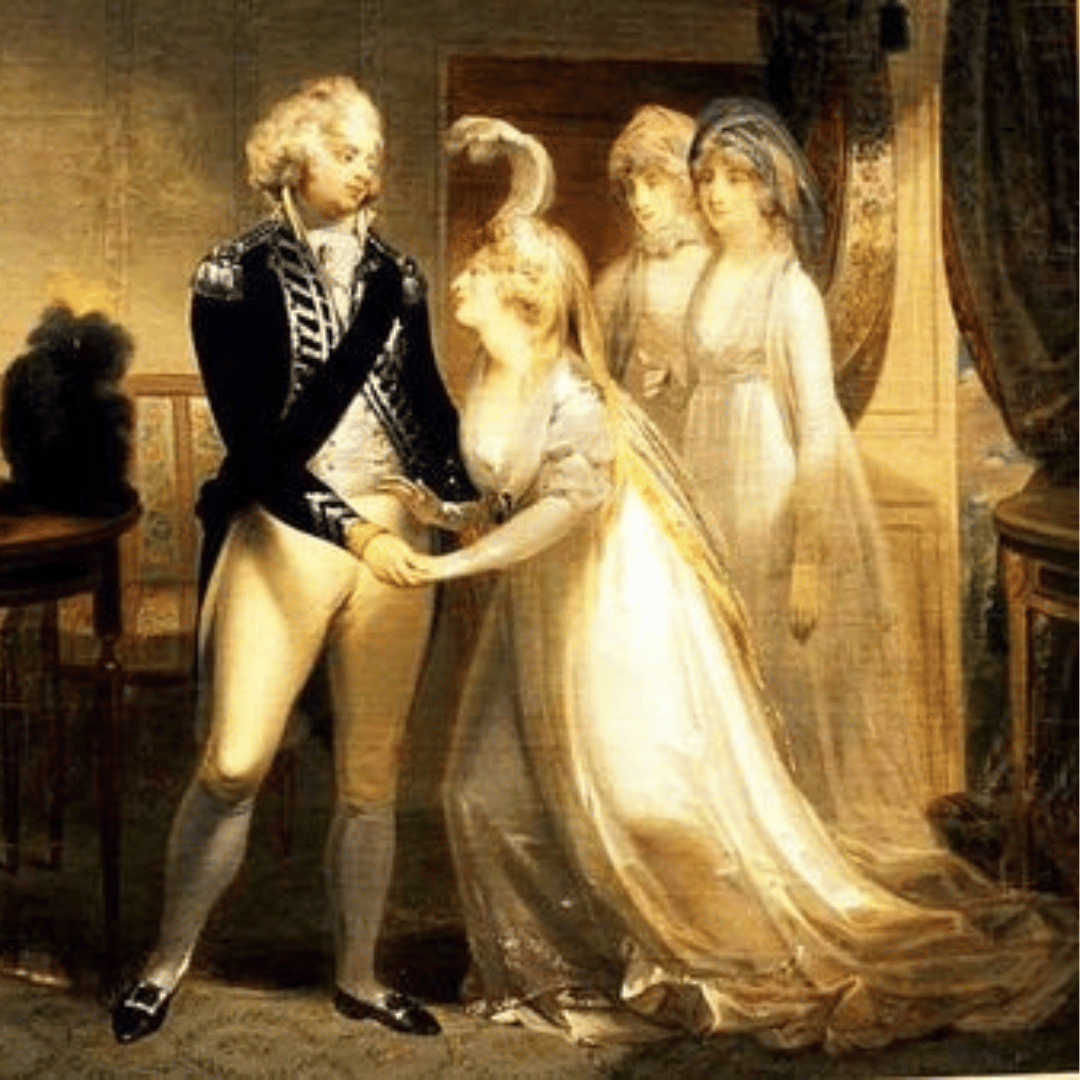

The story of the Staffordshire spaniel is tied to the history of the living, frolicking Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. During the Renaissance, these gentle, comforting little dogs were called Spaniells Gentle or Comforter Spaniels. Court ladies hid them under their voluminous skirts to keep their legs warm. Legend has it that a small black and white spaniel was found in the skirts of Mary Queen of Scots (1542-1582) after she was beheaded, according to Adele Kenny in her book Staffordshire Spaniels.

The spaniels became great favorites of the British monarchs. King Charles I (1600-1649) had a spaniel as a young boy. The court of his son, the Cavalier King, Charles II (1630- 1685), was full of his eponymous pets. Here are his children with their dogs:

Queen Victoria’s (1819-1901) tricolor spaniel, Dash, sat next to her on the throne.

Court painters featured him as the subject of portraits, and as a result the spaniel became a popular motif in paintings and pottery.

Since the 1720s, spaniels—along with other figurines, such as shepherds and princesses, lions and lambs—had been produced by pottery factories in Staffordshire. Thanks to Dash, however, the spaniels enjoyed a siege of popularity in the 1840s which lasted through Victoria’s reign (1837-1901). They became the quintessential Victorian bourgeois status-symbol knick-knack: no mantelpiece was complete without a pair of spaniels standing guard.

The Cotswolds Cottage of Luke Edward Hall

To meet the dog demand, factories enlisted underpaid, overworked children to paint the whiskers and splotches of “the only ‘pets’ they would ever know,” reports Kenny—a sad story, and unfortunately true. Although the vogue of the spaniels was at first glamorously royal and then virally bourgeois, the production of the spaniels descended to the smallest, poorest laborers.

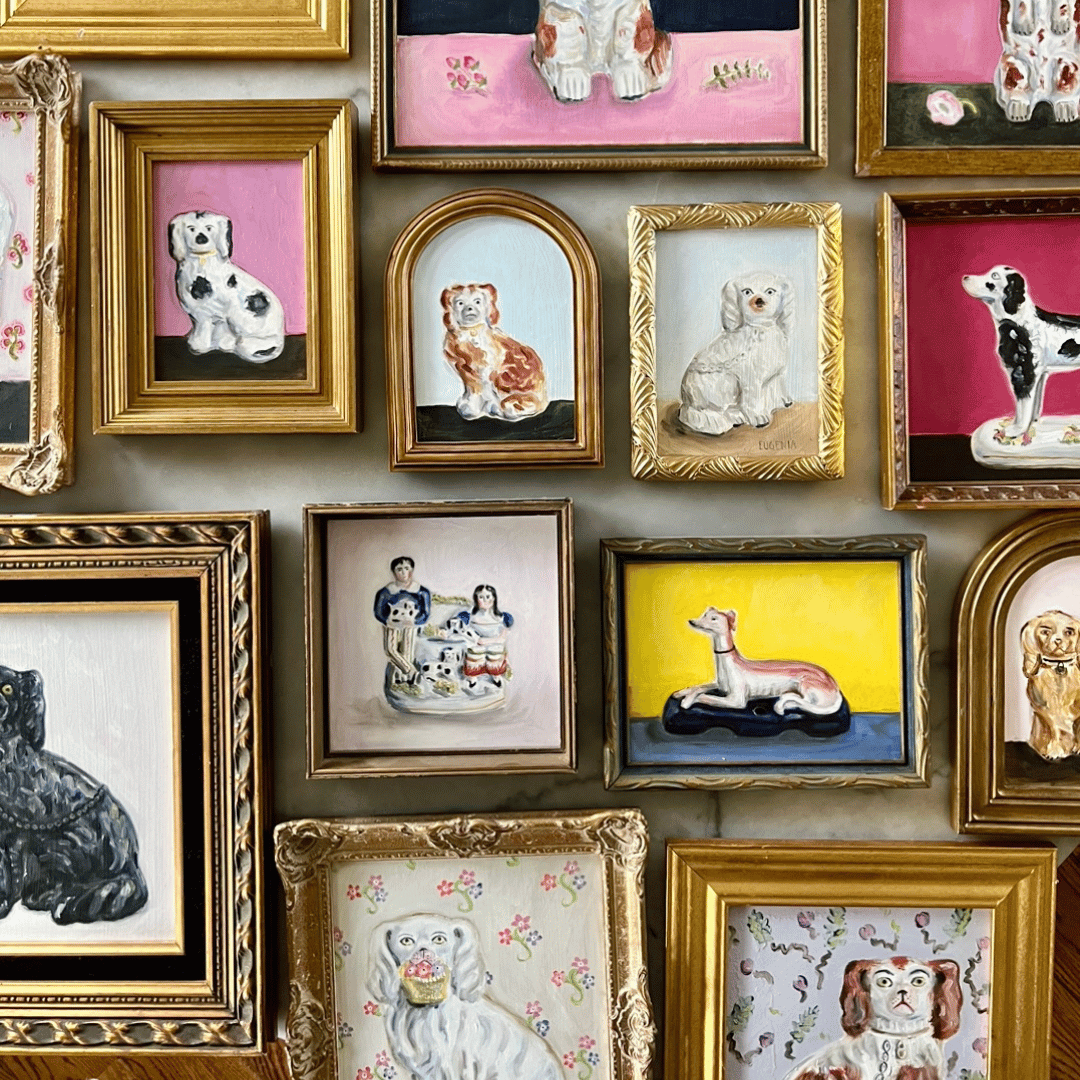

Most spaniels are simple variations on a theme: they have two ears, two eyes, and a smug little nose. Their base coat is a creamy white, rippled with texture. They sit with two paws in front, one visible beneath, and a fluffy tail curled around in front of them. Around their neck they each sport a collar and locket, with a chain leash hanging down and looping across their backs. The spaniels were produced in symmetrical pairs of canine soul mates, but today they are often found in lonesome singles.

If so many of the spaniels are based on this common model, then why are they so intriguing? Despite the shared elements, there is a great range of stylistic difference. The spaniels come in sizes from a little over a foot to a couple of inches high. The base coat is layered over with polka dots or brushed patches of rust, copper luster, or black. Disraeli spaniels feature painted curls on their foreheads; Jackfield spaniels are made of red clay and glazed entirely black. Some have painted eyes, some see through glass. The most frequent model features the front legs molded to the body, but rarer models have one or two distinct front legs. Some spaniels are standing on all four legs and ready to go for a walk, while others are lying down. A rare bunch of spaniels do more than just look pretty: they masquerade as such utilitarian objects such as spill vases, ring holders, banks, and pitchers. Although Cavalier King Charles Spaniels were the most popular, you can also find other Staffordshire dog breeds, such as pugs, greyhounds, afghans, collies, poodles, and Dalmatians.

In addition to these basic stylistic differences, each dog possesses a certain distinguishing, endearing uniqueness. Even in pairs of twins, no two dogs are the same. The real artistry is in the almost ineffable details which allow each pottery creature to come to life like no antique chair or table ever could. The dogs can be cuddly or fierce, whimpering or smug, curious or proud. There are stories surrounding the production of these antiques, but the best story a Staffordshire spaniel can tell comes from its own expression. We might try to imagine the look of the spaniels looking out from the window of the woman’s bungalow. Coy? Condemning? Or perhaps enigmatic?

Today, you can find spaniels up for antique adoption in boutiques, at flea markets and online. Although these dogs are relics of a long-passed Victorian vogue, they have also somehow managed to continue to resonate with modern sensibilities. We might pick up a dog or two for aesthetic reasons: their graceful silhouettes pop nicely against a dark background. Or we might collect them for their rarity: each one is a unique artifact and a valuable investment. We might be drawn to the dogs for their engaging expressions: buy a single one to be your ever-constant, patiently-listening best friend, or buy an entire pack to liven up the household. Or, finally, we might just bring them home with us because they are already surrounded by such wonderful stories and are sure to generate more: Staffordshire spaniels make great conversation pieces.

BUYER BEWARE! INDICATIONS OF FORGERIES INCLUDE:

- The bottom should be covered, not open. (There are a few exceptions, including some Jackfield, treacle ware, and early porcelain pieces, as well as some slip-cast model from the late 19th-century onwards.)

- Somewhere on the piece (usually on the back) there should be an air release hole; it should be about 1/8 of an inch, not larger.

- The base should be glazed, not chalky.

- The glaze should be crackled from age, not artifice; check that the crazing is neither too even, too complete, nor too obvious.

- The features of the dog should have life to them; they should be painted with detail and skill, but in such a way that the spontaneity of the brushstroke is still apparent. Check that the features are neither too deliberate, too heavy, nor too elaborate. Be especially wary of whiskers that curl into mustaches!

- In addition to all these separate indicators, an entire, authentic, antique spaniel possesses an indescribable je-ne-sais-quoi. Real spaniels have what Kenny calls a “spontaneous presence”—a cryptic formulation which won’t make much sense until you’ve known a lot of spaniels.

- Your chances of getting what you pay for are increased if you buy from a reputable dealer.

Collectors prize those spaniels that have been around the longest, but Staffordshire continues to breed authentic pedigree spaniels today, usually marked with some mention of “Staffordshire” or simply “Made in England” on the bottom. Although less valued as collector’s pieces, new, non-Staffordshire reproductions— like mutts—need homes too.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.